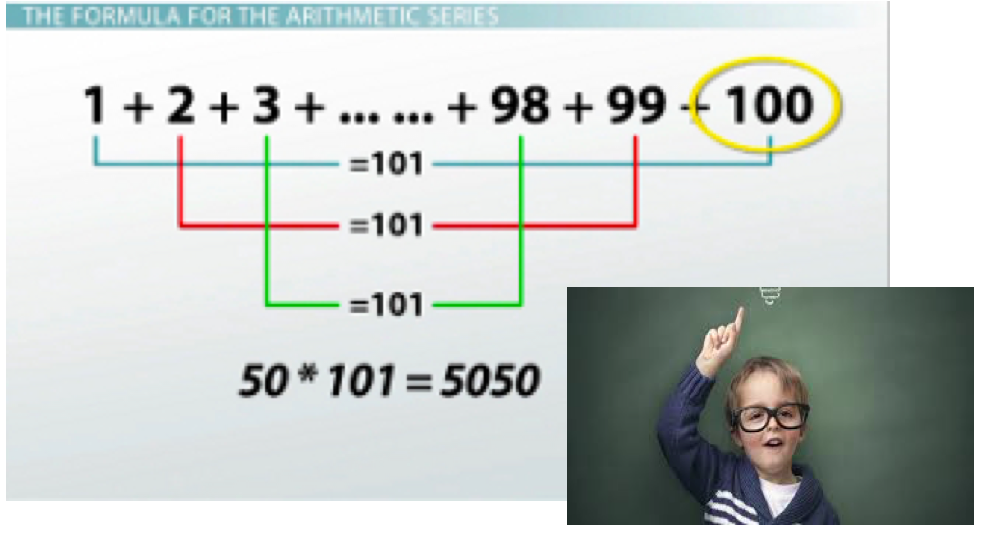

On a school day in the late 1700s, a teacher, for unknown reason, ordered her pupils to add up all the numbers from 1 up to 100.

The children immediately started adding except for the future prince of mathematics.

It took him a few seconds before he proudly announced the result.

What a glorious day for the little Carl Friedrich Gauss!

Fast forward to a hot summer day in the late 1970s. I was then a high school student. On that day, factoring was taught first, then an assignment was given:

“Factor all expressions on page 18, only 88 of them”

The students went to work immediately except for me who got a funny idea of doing something else.

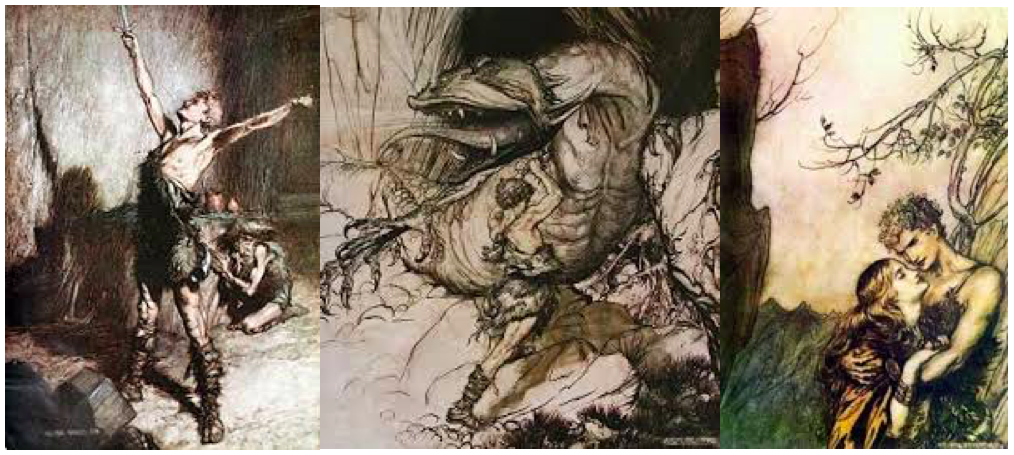

While pretending to be working, I was peeking though the illustrated book “Ring of Nibelungs” by Arthur Rackham. I brought it to school and hid it under the dull textbooks.

What a sixteen-year-old would rather do? Slaying dragon or factoring algebraic expressions?

Just as I was enthralled by the adventures of Siegfried, my hero, a voice boomed from behind:

“What are you doing rascal ?!”

It was the teacher.

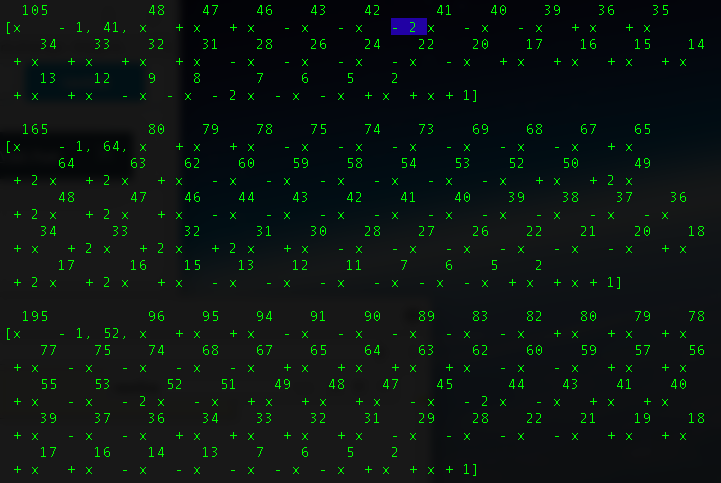

The punishment – Factoring , for

is the additional homework!

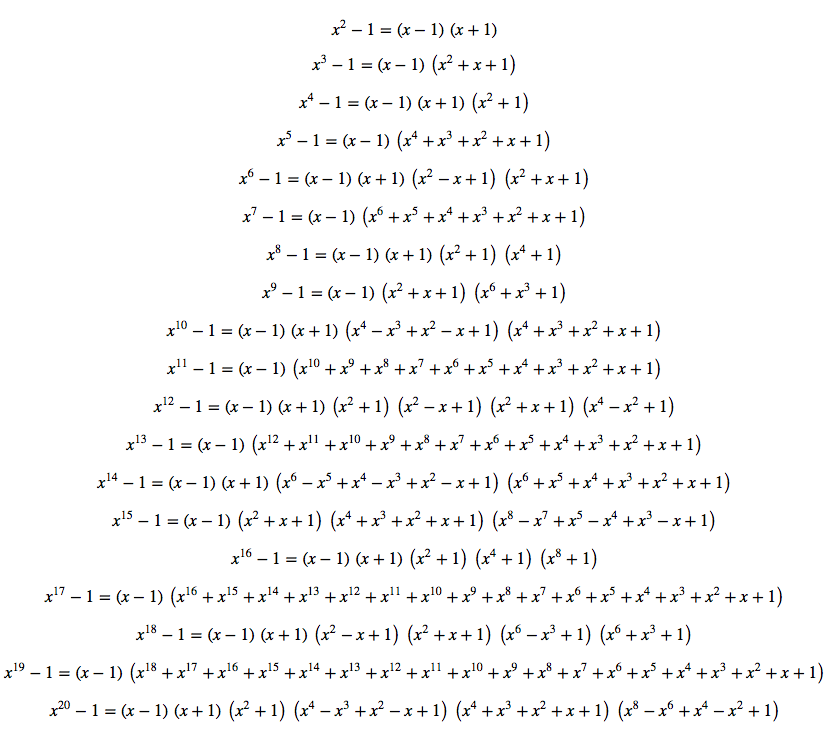

I managed to complete this before staggering into the bed:

As I was factoring, I made an observation:

The non-vanishing coefficients in any factor are either -1 or 1.

I wondered: Could this be true for all values of ?

As soon as I finished factoring , I wrote down a conjecture named after Siegfried:

The absolute value of all coefficients appear in the polynomial factor of is always 1.

That night I had a lucid dream, where I proved “Siegfried conjecture.”

Reviewing the proof in the morning, however, to my dismay, it was a pile of junk.

Still, for several weeks I continued my effort fervently, but I could neither prove nor refute “Siegfried conjecture”.

All to no avail. I had to give up.

Fast forward again to a mid summer day a few years later.

I visited Joe, a high school classmate who was studying at MIT to become an aeronautical engineer.

While walking on campus, I teased my friend: “How many basketball championships does MIT have? Do you even have any sports team here?”

Joe shrugged: “Haha, but we have created MACSYMA, the world’s first program that does symbolic algebra! Come, let me show you its power.”

That evening, I sat quietly in front of a VT100 tube, getting acquainted with MACSYMA.

It was fantastic. I felt as though I was brought out of the hold of a ship where I had lived all my life, onto the deck, into the fresh air.

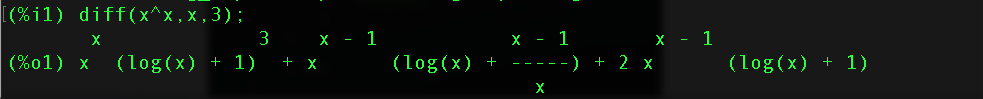

I saw the good –

Then the better –

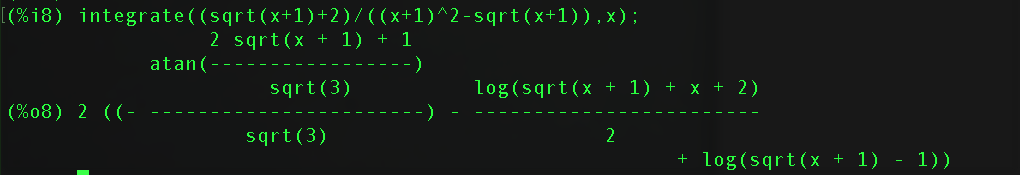

Finally the best –

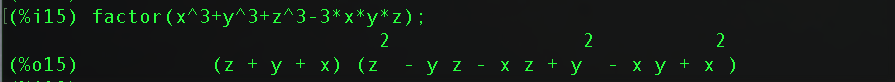

I grabbed the keyboard and commanded MACSYMA:

It responded:

At is the coefficient of term

.

In a blink of an eye, MACSYMA disproved “Siegfried conjecture”.

And I, while fully clothed, jumped up and shouted

Thanks to MACSYMA, the day was finally mine!

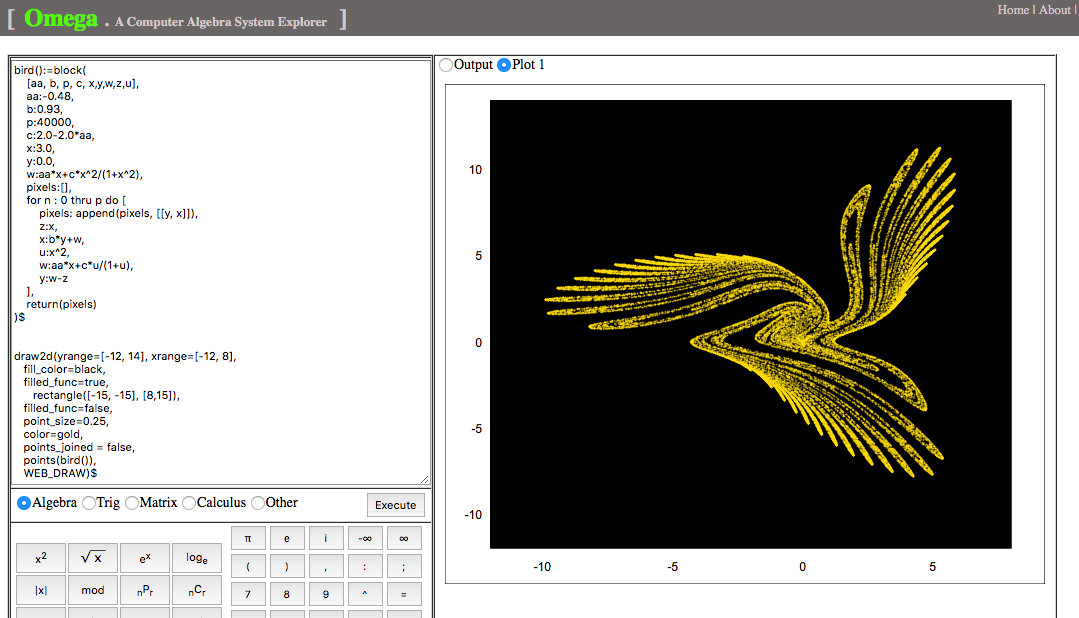

Fast forward once more to the summer of 2005, the spark MACSYMA lit in me twenty years ago gave life to Omega CAS Explorer:

Hooray! Every dog has its day!

Recently, as I was preparing for my talk at ACA 2017 (See “Little Bird and a Recursive Generator“), I looked at the formula

and wondered:

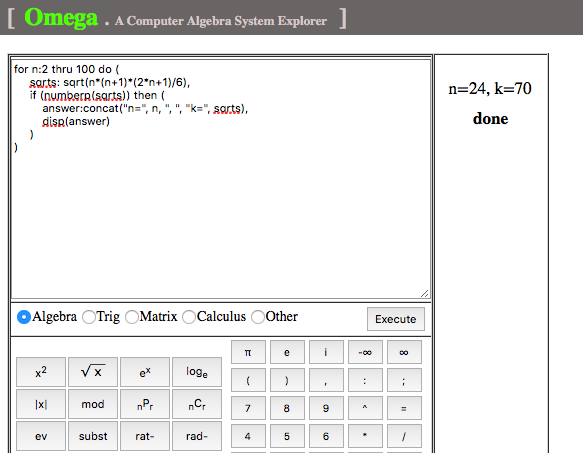

For what value(s) of , (1) produces a perfect square ?

A search shows when , (1) yields

, a perfect square:

But are there any other such ‘s?

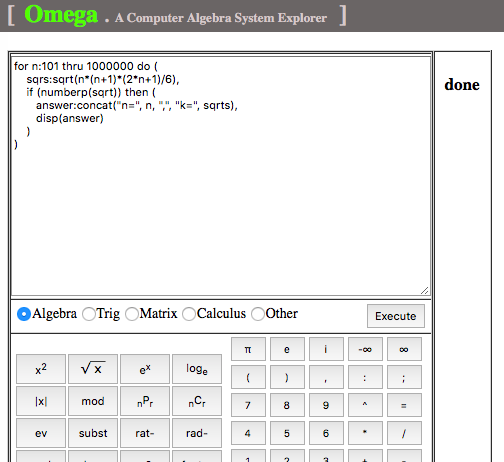

Further search yields no result:

It leads me to think:

For is the only solution to Diophantine equation

Can you prove or refute my new conjecture?